Rwanda’s coffee farmers push for organic standards amid regional market barriers

Coffee farmers in Rwanda say that the sector continues to grow and gain value through different farmer groups, including women’s cooperatives, although there are still challenges in accessing markets within East African Community countries.

Some of the farmers who spoke to Greenafrica.rw say that their coffee is in high demand mainly in countries outside the African continent, more than it is traded across borders within the East African Community (EAC).

Based on discussions held during a regional meeting of EAC countries on cross-border trade for agroecological products, which took place in Jinja, Uganda from October 27–31, 2025, Gilbert Muhire, the marketing and sales officer at Dukunde Kawa Musasa Cooperative in Gakenke District, highlighted challenges they still face in expanding their coffee business within the region.

He said: “Among the coffee we grow, some is organic while some is not. Organic coffee is grown using only manure and natural pest control methods without industrial chemicals, while some farmers use approved fertilizers and pesticides.”

Last year, the European Union announced that no product would be allowed into their market unless it was produced through environmentally friendly and biodiversity-friendly agroecological practices. Gilbert says their cooperative has already started aligning with these requirements so they can remain competitive in the international market.

He said: “We have started complying with this system, but challenges remain because we are required to send samples to their laboratories before approval, to confirm that no chemical residues are present. This becomes difficult because Rwanda does not yet have its own lab to test these products as part of training our farmers to ensure compliance.”

Gilbert said they expected the meeting to help resolve challenges related to the lack of markets within the EAC region, as many had been discussed, including taxes imposed by different countries, issuance of certificates, mixing organic and non-organic products, and language barriers among cross-border traders.

He said: “Although we export our coffee, we still do not have markets within the EAC. What we export to other continents is what we call GREEN coffee, which still needs one more step of processing before consumption. Yet we have the capacity to process and roast coffee so it’s ready for consumption. Fully processed coffee earns more profit than exporting it at the green stage.”

He added: “Coffee used to be exported to Europe for processing and then brought back to our region at high prices. We want to expand markets within the EAC so that our coffee reaches consumers directly, without passing through other continents. Being close to the market means consumers will buy it at a fair price, and farmers will earn more.”

The inability to visually distinguish between organic and non-organic crops is not a major challenge for the coffee business.

In cash crops like coffee, this is not a major issue because buyers rely on certificates of quality. In Rwanda, there is the S-Marker, which confirms compliance with national standards; other countries have similar certification systems. These agencies inspect the value chain from farm to final coffee product, testing soil or coffee leaves if necessary.

A farmer who complies with organic farming standards receives certification, and the coffee packaging carries a mark showing it is organic, so buyers know what they are purchasing.

This is different from perishable crops such as vegetables, fruits, and tubers, which spoil quickly. However, the meeting recommended that even these crops should be supported with proper certification from field to market.

In advanced markets like the United States, Switzerland, Italy, and others, products already carry labels showing how they were grown, allowing buyers to choose based on preference, budget, and quantity.

Non-coffee crops grown alongside organic coffee should also be valued.

Coffee farmers often intercrop with pumpkins, beans, potatoes, bananas, vegetables, or fruits such as avocados. The harvest from these crops is often consumed at home or sold cheaply compared to produce grown with chemical fertilizers.

Gilbert says these crops grown alongside organic coffee could generate more income if properly harvested, marked as organic, and sold at better prices instead of being treated casually. Their quality is high because they are grown without chemical fertilizers.

He said: “Crops intercropped with organic coffee should be given value. If it’s avocado, potatoes, or pumpkins, they are also organic because they were grown without chemical fertilizers. They should be harvested properly, taken to the market, and sold as organic products. Farmers who produce organic crops should be supported so that their produce gains value through institutions like ROAM and others in the region.”

Smuggling remains a challenge due to the possibility of forging certified labels.

Organic coffee certified for export carries labels that earn it value in international markets, including supermarkets. There is concern that some people might copy these labels and pack inferior coffee, leading buyers to wrongly blame the certified cooperatives.

Gilbert explained: “This has happened before. Not to us directly, but to others. Someone can take packaging that looks exactly like ours and fill it with poor-quality coffee. A customer who regularly buys our coffee may unknowingly buy the fake one and think Musasa’s quality has dropped.”

He added: “This can continue happening, but the regional meeting recommended that each country establish official centers for selling only certified organic products. We can also partner with supermarkets to create dedicated shelves so customers can easily distinguish our products.”

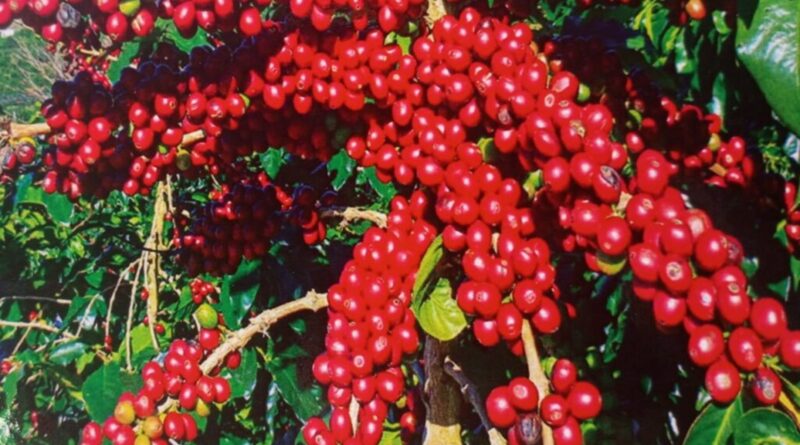

Dukunde Kawa Musasa coffee is unique because it is grown in high-altitude areas. The world’s most sought-after coffees are two types: Arabica, grown in highlands, and Robusta, grown in lowlands.

Arabica is known for superior taste, which is why Musasa’s coffee grown in volcanic highlands at an altitude of 2,200 meters is highly valued. The cooperative also has the equipment needed to process coffee from nursery to roasted coffee.

To support environmental conservation and respond to climate change, the cooperative aims to grow coffee alongside at least 12 species of trees to protect air quality, conserve soil, and provide fodder for livestock.

In high-altitude zones, coffee also helps prevent soil erosion, as shown in NAEB research, which describes coffee itself as a soil-conserving tree.

A coffee seedling takes eight months in the nursery before being transplanted, and farmers wait at least three years before harvesting. Rwanda has one main coffee season, harvested from February or early March through June, with small off-season harvests in August and September.

According to NAEB reports, one coffee tree produces between 2.5–3 kg of cherries, but with good farming practices, it can yield 10–15 kg. A member of Dukunde Kawa Musasa must have at least 300 trees. Using an average yield of 6 kg per tree, 300 trees produce 1,800 kg (1.8 tons). At a price of 1,200 Rwf per kilogram of cherries, a farmer earns at least 2,160,000 Rwf per year.

Dukunde Kawa Musasa Cooperative began in 2000 with 300 smallholder farmers who united to access international markets and fight middlemen who exploited coffee growers. This matched Rwanda’s policy encouraging farmers to form cooperatives to reach larger markets.

Today, 90% of the cooperative’s coffee is exported. Each year they ship about 12 containers, each with around 19,200 kg. They plan to strengthen women’s and youth cooperatives to encourage them to join coffee farming, although most current farmers are older, with an average age of 59.