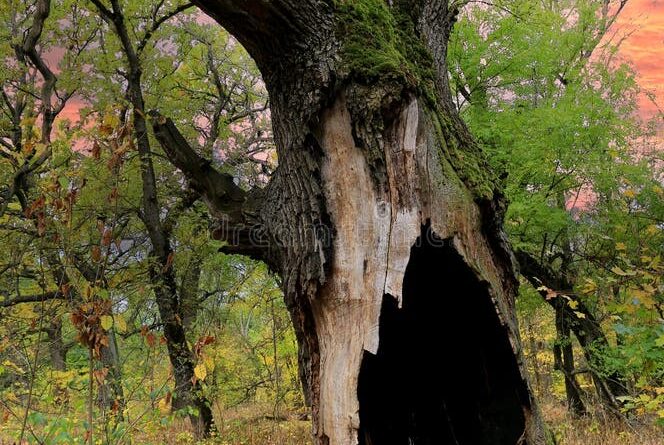

Deadwood Is not a waste: A pillar of forest life and biodiversity

While some community members continue to view deadwood in forests as useless material suitable only for removal, burning, or charcoal production, forestry experts and environmental scientists emphasize that deadwood is a cornerstone of forest health, biodiversity, and sustainable ecosystem functioning.

Deadwood,whether standing (snags) or lying on the forest floor (fallen logs),plays a critical ecological role by providing habitat for diverse species, improving soil fertility, and supporting natural forest regeneration.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), in its 2020 report, identified deadwood as an essential structural component of forest ecosystems.

FAO notes that “deadwood is a vital element of forest ecosystems, supporting biodiversity, enhancing soil nutrient cycling, and enabling forests to regenerate naturally.”

The report further warns that forests from which deadwood is systematically removed lose their ability to self-renew, retain nutrients, and build resilience against climate change impacts.

Biodiversity specialists explain that deadwood serves as a lifeline for numerous organisms, including insects, fungi, reptiles, amphibians, birds, and small mammals. As trees fall and decay, they create microhabitats that provide shelter, breeding sites, and feeding grounds.

As decomposition progresses, deadwood gradually transforms into organic matter, enriching the soil with essential nutrients, improving moisture retention, and enhancing soil structure. This process creates favorable conditions for seed germination and forest succession.

Forest ecologist Dr. Peter Wohlleben, in his book The Hidden Life of Trees (2016), underscores the ecological importance of deadwood.

He explains that “deadwood is not lifeless; it is among the most biologically active components of a forest, sustaining countless organisms that keep forest systems functioning.”

This highlights that forest vitality extends beyond living green trees and depends on continuous interactions among deadwood, soil organisms, microorganisms, and wildlife.

In forests inhabited by large mammals such as elephants, researchers highlight the animals’ significant role in generating deadwood and shaping forest structure. Elephants frequently push over trees,especially weakened or young ones,creating fallen biomass that becomes shelter and nutrient sources for other species, including snakes, rodents, insects, and birds.

Over time, this elephant-generated deadwood decomposes into natural forest fertilizer, increasing soil fertility and stimulating vegetation growth. For this reason, ecologists widely refer to elephants as “ecosystem engineers” due to their capacity to modify habitats and sustain biodiversity.

Emelance Tuyipfukamire, a Research Support officer specializing in elephant ecology at Akagera National Park, explains that elephants are a defining ecological force within the park.

She notes that elephants, one of the iconic Big Five species, actively engineer forest landscapes by uprooting trees, which allows grazing species such as impalas and antelopes to access low-growing vegetation.

She further explains that although elephant activity may appear destructive, it actually promotes tree species diversity.

When elephants knock down trees, seeds are dispersed across wider areas, encouraging regeneration and preventing forest dominance by a single species. This process enhances structural and biological diversity.

Trees transition into deadwood through natural ecological processes, including senescence, lightning strikes, fungal infections, insect infestations, disease, and extreme climate events such as prolonged droughts or intense rainfall. These processes are integral to forest life cycles.

A 2018 study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) shows that elephants play a crucial role in seed dispersal. Seeds passing through elephant digestive systems often exhibit higher germination success.

According to IUCN, “elephants significantly enhance seed dispersal and habitat modification, strengthening forest regeneration and ecosystem resilience.”

As a result, landscapes containing elephants and sufficient deadwood tend to support richer biodiversity and stronger regenerative capacity.

Despite extensive scientific evidence, some community members continue to view deadwood as wasted material suitable only for firewood or charcoal.

Forestry experts caution that this perception poses serious risks to forest ecosystems. Professor Chad Oliver of Yale University stated in a 2019 lecture that removing deadwood disrupts natural regeneration processes and reduces long-term forest productivity.

Jean Paul Karinganire, a funding and reporting manager, cooperation between the park and local communities, emphasizes that deadwood and elephant activity are fundamental to sustaining biodiversity, including the Big Five species.

He explains that in Akagera, elephant-generated deadwood provides shelter and nutrients essential to ecosystem stability. When deadwood is removed, the entire ecological balance is compromised.

He adds that protecting deadwood and conserving keystone species such as elephants enhances landscape integrity, strengthens ecotourism, and contributes to national economic development and sustainability.

Researchers conclude that conserving deadwood and ecosystem-engineering species is not an obstacle to development but a long-term investment in resilient forests, biodiversity conservation, and human well-being.

They emphasize that strengthening science-based awareness and implementing evidence-driven environmental policies are critical to ensuring forests remain a sustainable foundation for future generations.

In quantitative terms, Rwanda has made significant progress in forest restoration. Government data indicate that forest cover now exceeds 30% of the country’s total land area, up from approximately 23% just over a decade ago.

Through its commitment to the Bonn Challenge, Rwanda has pledged to restore more than two million hectares of degraded land by 2030, including forests, agroforestry systems, and erosion-controlled landscapes.

Each year, at least 100 million trees are planted nationwide through coordinated efforts involving government institutions, development partners, and local communities,demonstrating that Rwanda’s forest restoration strategy is grounded in measurable action, ecological science, and long-term sustainability.