Papal election Smoke: Chemistry, meaning, and environmental effects

During the election of the head of the Catholic Church (Pope), people around the world turn their eyes to the roof of the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, waiting for a signal of smoke.

Black smoke (fumata nera) or white smoke (fumata bianca) are the signs that indicate whether a new Pope has been elected or if voting is still ongoing.

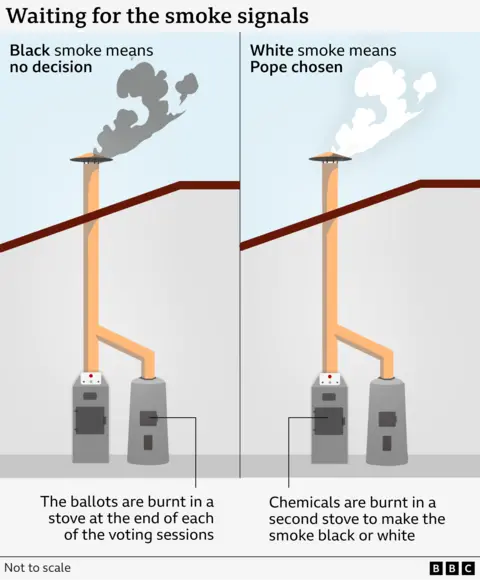

The smoke rises through a temporary chimney placed on top of the Sistine Chapel. This chimney is connected to an iron stove located inside the chapel. It has two main components:

The first stove is used to burn the ballot papers from the election.

The second stove is used to burn chemical compounds that produce either black or white smoke, depending on the outcome of the vote.

Both stoves are connected to a single outlet pipe so that observers outside the chapel can clearly see the results.

Since 1417, ballots have been burned after each round of voting. In the 18th century, the use of a temporary chimney on the Sistine Chapel was introduced.

In 1914, white smoke began to be used as a sign of the successful election of a new Pope. And in 2005, specially formulated chemicals started being used to make the smoke more visible and eliminate confusion.

Although this smoke may seem ordinary, it is actually made up of a complex mixture of chemical compounds, rooted in historical tradition, and carries significant symbolic meaning for the Catholic Church. But how exactly is this smoke made? And what are its environmental implications?

The smoke used in papal elections is one of the Church’s most iconic and symbolic traditions. Black smoke signals an inconclusive vote, while white smoke indicates that a new Pope has been elected.

Research from McGill University in Canada has revealed that the smoke is not generated randomly but through a carefully crafted blend of chemicals designed to produce distinct colors and a clear message to viewers.

According to a 2013 article in The Telegraph titled “The smoke is made using a secret chemical recipe that has been tested to ensure it does not pollute or confuse”, and a report in The Guardian in the same year, “The Vatican now uses smoke cartridges specially designed to create clearly visible black or white smoke without environmental risk”, the Vatican uses highly controlled chemical mixtures to ensure clarity and safety.

These sources detail the chemical composition used to produce each type of smoke:

The Chemistry of Black Smoke (Fumata Nera), Potassium perchlorate (KClO₄), An oxidizing agent that releases oxygen when heated. It enables better combustion of fuel-based compounds. Reaction: KClO₄ → KCl + 2O₂

Anthracene (C₁₄H₁₀),A polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. It burns incompletely to produce black carbon soot, creating a dark, visible smoke.

Sulfur (S) – When burned, it produces sulfur dioxide (SO₂) and contributes heat to regulate the reaction. S + O₂ → SO₂

These compounds work together to create thick, black smoke visible in the sky.

The Chemistry of White Smoke (Fumata Bianca), Potassium chlorate (KClO₃) – Another oxidizing agent that releases oxygen to assist combustion. 2KClO₃ → 2KCl + 3O₂

Lactose (C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁) – A disaccharide (sugar) that, when burned, releases water vapor (H₂O), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and fine white soot. C₁₂H₂₂O₁₁ + 12O₂ → 12CO₂ + 11H₂O

Rosin (colophony) – A resin derived from pine trees, rich in diterpene acids like abietic acid. It burns slowly, releasing fine white aerosols that appear as white smoke.

These chemical properties are supported by foundational organic chemistry texts such as: Morrison & Boyd (2011), Organic Chemistry (Pearson).

Atkins & Jones (2010), Chemical Principles: The Quest for Insight (W. H. Freeman)

According to a 2015 UNEP Environmental Report, activities like this should be “carbon-neutral” whenever possible.

Due to the high heat involved, mishandling these chemicals could pose risks. Therefore, the Vatican Office for Technical Services, along with publications like L’Osservatore Romano and Vatican News, offers detailed technical explanations on the smoke procedures during the Conclave.

They explain that the Vatican is meticulous about the combustion process, using approved and tested materials monitored by experts, including Vatican Gendarmerie (special police) and the office responsible for Vatican infrastructure.

Environmental inspections are carried out around two to three weeks before the election.

In 2013, Fr. Federico Lombardi, then Vatican spokesperson, stated that “the smoke will no longer cause confusion or pollute the air.”

In past years, unclear or poorly made smoke caused public confusion, especially in the elections of 1958, 1978, and 2005, where it was difficult to distinguish black from white smoke.

As a result, in 2005 the Vatican assembled a team of chemists and technicians to develop a modern, efficient smoke formula that would produce clear signals and eliminate doubt.

During a papal conclave, cardinals vote in secret, and ballots are burned to signal the election’s progress:

The Pope is elected inside the Sistine Chapel, built in the 15th century (1473–1481), located in the Vatican. The rising smoke from the chimney announces to the world whether a new spiritual leader of the Catholic Church has been chosen.

According to BBC Future, black smoke may be generated by burning ballots with added diesel or carbon, creating soot similar to charcoal smoke. This increases the visibility of the black smoke.

On the other hand, white smoke is produced by burning a mixture of potassium chlorate (KClO₃), lactose (milk sugar), and rosin (a pine tree extract). This carefully measured blend creates a stable white smoke that signals the successful election of a new Pope to people all over the world.

Though the amount of smoke produced is minimal compared to emissions from factories or vehicles, environmental experts remain cautious. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the chemicals involved can have minor effects on air quality,especially if the election lasts more than three days.

This raises concerns at a time when the world is facing climate change, and the Catholic Church itself has shown its commitment to environmental protection particularly through Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato Si’.

Therefore, although the smoke is used occasionally, analysts suggest adopting modern alternatives that can communicate the message without harming the environmental filter.

This smoke was modernized after confusion arose over its color during the announcement of some papal elections.

While the chemicals used can have environmental impacts, the Vatican has implemented measures to minimize these effects, including: Using verified substances: The selected compounds produce clearer smoke with less atmospheric pollution.

Improved combustion techniques: Efficient burning methods ensure the smoke is visible but less harmful.

Shorter smoke release times: The smoke is released for a very short duration, minimizing environmental damage.

Experts have also noted that this smoke is not emitted frequently. It is used only during the election of a new pope a process that doesn’t happen regularly.

The smoke is also used in papal elections in 1878, where it gained a unique symbolic meaning. Later, in 1903 and 1939, new techniques were introduced to send clearer signals, including what became known as “signal smoke.”

Since 1963, a more modern system has been adopted, using specially formulated organic compounds to help clearly distinguish the smoke’s color.

Historical examples, such as the elections of Pope Benedict XVI in 2005 and Pope Francis in 2013, show faithful crowds gathered in St. Peter’s Square, eyes fixed, hearts expectant—waiting for that white smoke to emerge.

The smoke used in papal elections is not a routine act. It is a fusion of science, history, and faith, representing one of the most powerful voices on earth. Yet it’s also a ritual that must continually be reimagined with sustainability in mind. As a moral compass, the Church has the opportunity to lead by example in adopting technology that does not harm our shared planet.

In a world increasingly alarmed by pollution from factories, vehicles, and other sources, even small acts can play a role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Thus, the smoke from papal elections could become a catalyst for reflection and change, a way to deliver a powerful message through environmentally responsible means.

After the death of Pope Francis on April 21, 2025, 133 cardinals gathered for the papal conclave, held from May 7 to 8, 2025, in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican. After four rounds of voting, on May 8, white smoke (fumata bianca) appeared at 6:07 p.m. (CEST), signaling that a new pope had been chosen.

Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost, born in Chicago, United States, was elected and chose the name Pope Leo XIV. He became the first American to be elected as head of the Catholic Church. He appeared for the first time on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica, greeting the gathered faithful in St. Peter’s Square with the words: “Peace be with you all!”

The way the election of Pope Leo XIV unfolded demonstrated that the Vatican had made significant efforts to use modern methods for producing clearly visible smoke, avoiding the confusion experienced in previous years. This confirms that the signaling process during papal elections continues to evolve in line with the times while still preserving the Church’s culture and rich tradition.